Placing a value on something that exists in a quantity of only one is tricky business. If there’s no history of a prior sale of the one item, say for a piece of art for example, the initial value (price) is solely determined by the seller, or in this case the artist. For other items that aren’t hand made by famous artists, value can be determined in one of the following transaction formats:

1. The seller places what he or she deems as an appropriate sale price and the market either accepts or rejects it. This option can go one of three ways:

- The item is sold over market par

- The item is sold under market par

- The item doesn’t sell at all

Market Par refers to what the market deems as an appropriate price for an item.

It’s possible for the item to be priced accurately but accuracy is seldom when pricing a 1/1.

2. The seller places what he or she deems as an appropriate sale price with the option for the market to place offers for the seller to field bids.

- This option entertains some leeway with regard to buyer choice. While prices generally start much higher than market par, the option to place competitive offers is always desirable. Items with singular print runs are commonly listed this way. It allows the seller to assume immediate higher returns over the general uncertainty associated with auction-style auctions. Some might think returns will always be stronger in this format given that prospective buyers will immediately assume higher value with larger starting numbers.

- Sometimes in these situations, a bidding threshold exists where offers won’t even be considered unless they’re at some minimal amount. This isn’t uncommon and in a way expected both to save time and field serious bidders. This is commonly preferential.

3. The seller places the item up for sale auction-style with a $0.99 starting bid and lets the market determine the final value.

- Something is only worth what someone is willing to pay for it.

- This is the most desirable but generally least common option, especially for inexperienced sellers. In situations such as this, the seller risks what he or she may think is commonly known as leaving money on the table. Thing is, if you let an auction ride, the market will determine the final value. This is the very nature of an auction.

In a lot of ways, how much you bid or ultimately pay for something is up to you. If you see a 1/1 available online with an asking price of $350 with a Best Offer option, take a stab at it and see where it takes you. 1/1s are interesting animals because they are, by their very design, once in a lifetime encounters.

Rhetorically speaking, can you place a value on a once in a lifetime encounter?

For situations like this, I consider the card and the price. If the price is what I deem to be way beyond realistic and there isn’t a Best Offer option, I pass. If, however, the price is reasonably high and there’s an option to place an offer, I do what I can to make arrangements. I won’t bother with overzealous sellers because in my experience some of them are out to flip in an attempt to make huge returns. Let me give you an example:

Let’s say a buyer acquires a 1/1 for $300 and then immediately re-lists it for $1500 (yes, I’ve seen this happen), the buyer is attempting to make a 500% ROI. That’s a hefty return if it sells, which might be a rare instance if it happens at all. However, given the buyer acquired it for $300, the market value for that item is in fact $300.

Now let’s say the buyer re-lists it for $600 with a Best Offer option. The market is much more willing to work around those parameters even with an understanding of the existence of a previously recorded sale of the same item for $300. The reason being is that many collectors respect the free market economy and the right to make money. I get that; I do.

However, as with anything, there’s a limit. If a buyer is only out to gouge the market by buying at market par and attempting to re-sell at near insulting rates, this is tacky and can compromise market stability contributing to volatility.

I understand that buying power is a critical factor in that all costs are relative to the amount of funds available at the time of item discovery. For buyers with ultra deep pockets, $1500 might not matter even with an understanding of the existence of a previously recorded sale of a fifth of the asking price.

If you come across a 1/1 that interests you, think about the transaction format and how it relates to both your buying power and level of desire to have the item. This will help facilitate your decision to acquire or attempt to acquire the item.

To shop for 1/1s, click here.

Have you visited our store? Click here.

Have you visited our store? Click here.

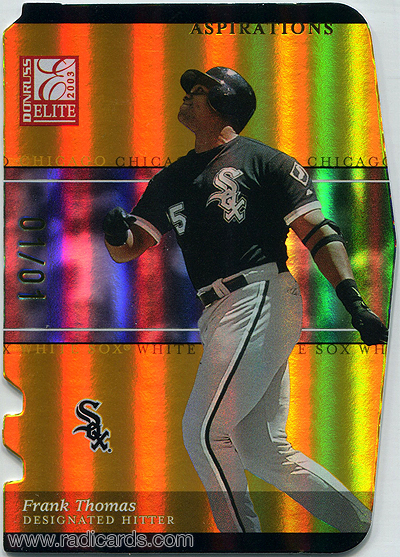

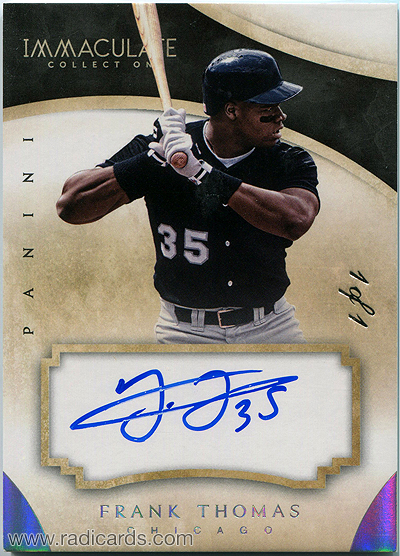

I agree that appraising 1/1 cards can be tricky. To help me judge fair market value of a particular 1/1, I’ll look to see if any other 1/1’s of a given player have sold recently. Even though other 1/1’s are from different sets, information can be gained and utilized. The thing is, in the modern card market, there are actually a relative surplus of 1/1 cards floating around (I know, sort of any oxymoron but it’s true).

I actually think cards numbered to about 10 to 25 or so are a little bit more interesting to evaluate. A card with a print run of 10 is still extremely limited, but with multiple copies in existence, the market has more chances to work its magic.

Checking if similar 1/1s have sold of a certain player is a good strategy. This can help sellers identify sell price but as you know, not all sellers bother with this strategy and many of the one’s that do may attempt to double their asking price to pull as much out of it as possible, which happens. As always, great comments, Brian. Thank you for reading and commenting.